Making algorithmic thinking a core skill

A while back, some were calling coding a “new literacy.” With the advent of AI, the world seems to be leaning away from that. But what hasn’t disappeared is the need to strengthen the kind of thinking that coding requires. Whether we call it computational literacy, or algorithmic literacy, AI is a tool for solving problems, but humans are likely to remain the scopers and designers of the problems that AI will solve.

If we want to consider how to make this computing skill set more universal, let’s look at what worked and what didn’t in one literacy program of yore.

Case Study: Literacy in the U.S. colonies

In 1642 the colony of Massachusetts made literacy the law. A harsh law. For five years, children unable to read The Bible could be taken from their parents. By 1647, however, faced with the reality that literacy wasn’t something that could be quickly legislated into reality, blame and responsibility shifted elsewhere (demonic forces, local government). In 1647, The Old Deluder Satan Act required that townships of 50 or more households were required to hire a teacher.

Unfortunately for these teachers, while The Puritans were big on literacy, they were not as crazy about books. For a full 40 years, the bible was the only book teachers could use, until the publication of the first edition of The New England Primer in 1688.

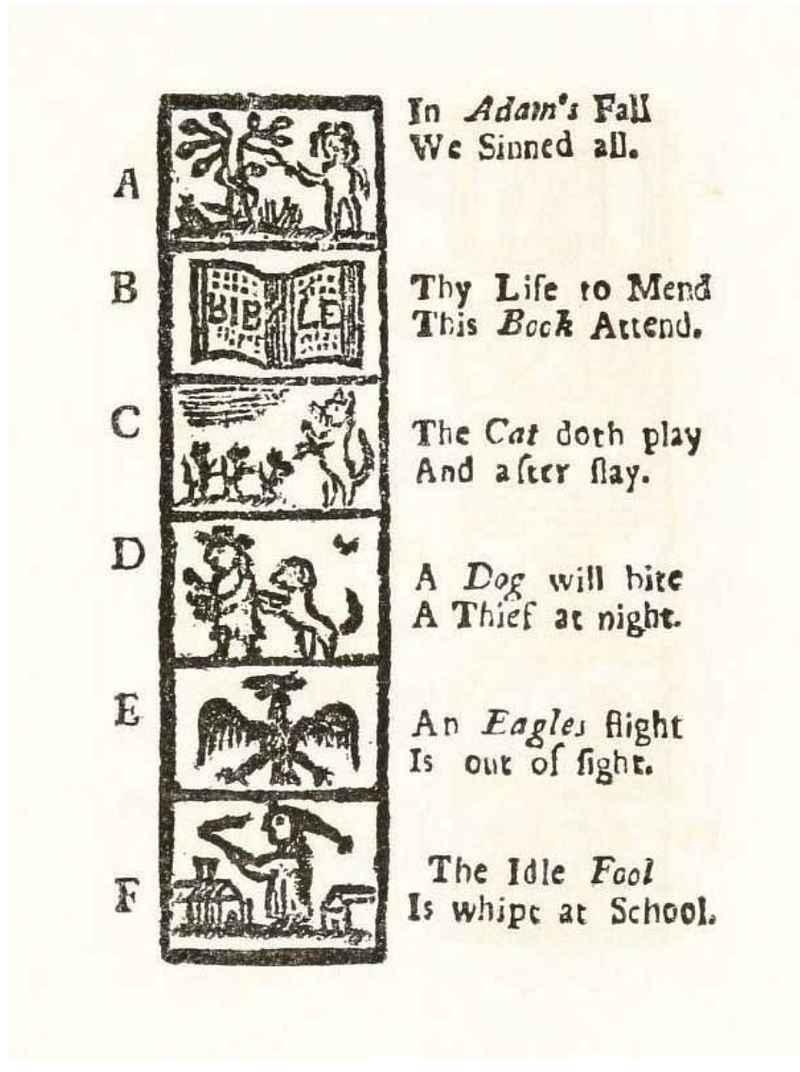

As we can see, from its somewhat infamous illustration of the alphabet, these were different times. We have not continued the practice of introducing children to the letter “A”, via the concept of original sin.

“F” will never again be for “The Idle Fool” who is whipped at school, because that is now illegal in most parts of North America.

C is still, as it may always be, for the playful cat, who “doth play,” before it slays. Though, we rarely bring attention to the fact that cats probably still believe to this day, they are torturing their toys.

Whatever we think of this pedagogy, the impact metrics on this primer were impressive.

Over the next century it would become the dominant textbook in the colonies, with 450 different adaptations. By 1776, the year of the revolution, 80% of Americans could read, compared to only 35–40% of England. This wasn’t because England didn’t have printed material. All the earliest best sellers (Gulliver’s Travels, Robinson Crusoe) had been published. Print was abundant, and libel laws were loose. Mid-18th century was the cultural equivalent of our glorious internet. It seemed like everyone was reading, writing, arguing under multiple pseudonyms. But in truth, quality education was still only available to the privileged.

So what was working in the American colonies? There were obvious strengths to the Primer. It was simple, memorable, adaptable, and seeded communities of practice that were held together by a strong belief system. But something stopped working, eventually. By the beginning of the 20th century, all the editions started disappearing from classrooms.

The obvious weakness was that its punitive pedagogy was not sustainable. The New England Primer remained in print only as long as that belief system remained dominant.

Towards a new literacy, and a new belief system

So if we want any new literacy to thrive and survive, we need a belief system that’s ultimately stronger.

What belief could drive us towards the creation of a society in which everyone, or almost everyone, knows at least the basics of how to code? What could be strong enough to meet the urgent need to become better citizens more empowered to understand the potential, but also the issues embedded in a world driven by AI, digital networks, data, and the ability to learn as fast as the world is changing?

What if we were to believe that computing is kind of the opposite of original sin? An original power. A power that has long preceded the invention of computers, and one of our most deeply rooted, most creative and most effective human abilities. What if we were to see it as an ability that we already, pretty universally share, whether or not we have access to the latest, or any technology?

If we believe this, then we can see coding as one of the better ways to strengthen and enrich that natural power. In the same way that reading and writing ultimately strengthen our power to reflect, create and democratize our world. Whether we call this power computational or algorithmic thinking, we could harness and value its full diversity. We could strengthen it to show each other no matter who we are, where we live, or where we came from, what we can do.

What if we kept believing this for the coming centuries, because it turned out to be true?

Maybe we’d find ourselves like the cat:

Always playful.

Always sharp and focussed enough to slay, even if we never need to again.

Always surviving, and always finding our centre in whatever iteration of new knowledge we happen to find ourselves in.

Further reading

The Algorithm Literacy Project

Leave a comment